Taking stock of the green revolution in Africa

Two sides battle over the future of farming in Africa

Welcome back to Food Adjacent! This week, Kigali is hosting the African Forum for a Green Revolution. The meeting prompted a slew of emails and articles both attacking and defending green revolution policies. At the center of fire is AGRA, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa. Below we look at what AGRA is, the controversy of the green revolution and who really benefits. Please like and comment!

A Green Revolution for Africa

As this week’s big African Forum for a Green Revolution approached, my inbox filled with campaigns against AGRA, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.

African Farmers and Faith Leaders Demand an End to the Failed Green Revolution, says one. USAID: Defund AGRA, Support Small Farmers, says another.

AGRA increases reliance on expensive and toxic chemical inputs, privatizes seed systems, increases farmers’ indebtedness, and fails to produce higher yields in the long term. A donor-commissioned evaluation has confirmed that AGRA has failed to meet most of its goals related to farmer impact. At the same time, AGRA (along with US philanthropic foundations and agribusiness corporations) has influenced African governments, encouraging them to pass […] policies that infringe on farmers’ access to seed, push imported farm inputs, enable profiteering by the fertilizer industry, and undermine efforts to boost self-sufficiency.

So what’s going on?

The story of the green revolution is as good as any fairy tale. We have a hero – the pragmatic scientist and Nobel Prize winner, Norman Borlaug. We have the bad guys – exploding population growth and hunger. Then a happy ending with “more than a billion lives saved!”

The moral of the story is the power of science and technology to save us from ourselves.

It’s in this spirit that governments and donors pursued a green revolution for Africa* – one based on commercial inputs (mostly improved seeds and fertilizer) to increase crop productivity, reduce hunger and tackle poverty across the continent.

As a result, the Gates and Rockefeller Foundations set up AGRA in 2006. But in the 16 years since its founding, AGRA has become one of African agriculture’s great bogeymen.

An ideological clash at a critical time

When the President of AGRA, Agnes Kalibata, served as the UN Special Envoy for the Food Systems Summit last year, 600 members from civil society and academia signed a letter to encourage a boycott of the summit. They accused the Summit of furthering the “corporate colonization of food systems” to the detriment of farmers, food workers and eaters. Not only did they boycott, but activists organized a “counter summit” during the official events.

In turn, these organizations are attacked as anti-science and out-of-touch with reality. They are accused of romanticizing subsistence farming and working against the real interests of smallholders.

Current events make the controversy even more salient. Inflation, supply chain challenges, and the war in Ukraine have led to high rising food prices. As a result, governments are once again turning their attention to local food production and helping smallholders be more productive.

But with climate change, increasingly inequality, and environmental degradation, many are arguing it would be a mistake for governments to continue down the path of industrialized agriculture. The green revolution has failed, they say, and it’s time to try something else.

What does AGRA even do?

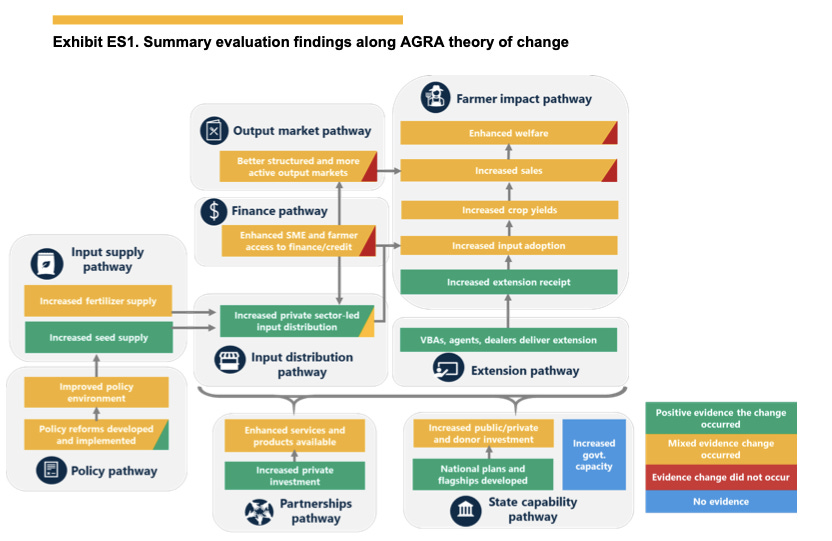

Founded as a non-profit, AGRA aims to create strong commercial input and output markets to “catalyze an inclusive transformation in smallholder agriculture.” It set ambitious goals for itself: to double crop yields and incomes for 30 million farming households by 2020.

While the organization has shifted countries and strategies through the years, it now works in Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Malawi and Mozambique with three main areas: policies to create a better regulatory environment for seed and fertilizer industries, partnerships with public and private actors to develop and disseminate new seed varieties and fertilizer blends, and country-specific programs to improve value chains and educate farmers.

They do this mostly by providing assistance to governments on policy, awarding grants to institutions and public-private mechanisms, and convening stakeholders (like the Forum this week).

How effective is AGRA at doing it?

AGRA reports that they’ve trained 15 million smallholder farmers to use commercial inputs, contributed to developing 659 new seed varieties across 18 crops, trained 680 PhDs and MSc students, and supported 40,000 agro-dealers and 1,628 small agribusinesses.

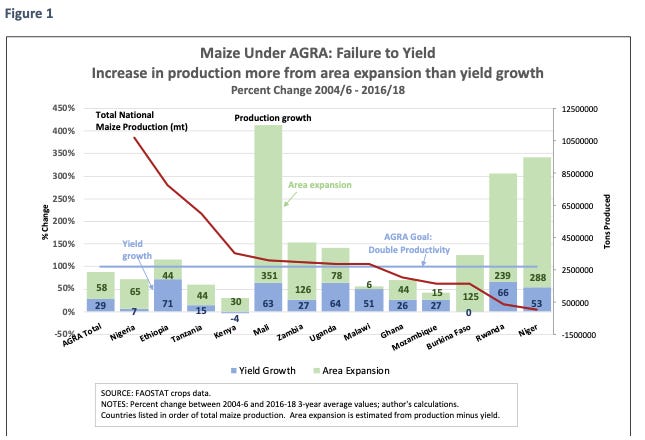

All very positive. However, you might notice this doesn’t mention progress on the big goals for crops yields and incomes. Outside evaluations (both with AGRA cooperation and without**) at its 2020 milestone moment found that the goals were not achieved. In fact, an external evaluation from Tufts University (without AGRA cooperation) suggests that AGRA may have even caused harm in some areas.

The Tufts report claims that the increase in staple crop production came at the expense of food crops and often on land poorly suited to the purpose. For small farmers, the cost of adopting commercial inputs was too high – leading them to either not adopt them or with little positive impact on their welfare.

Finally, it found that the crop productivity only increased slightly for targeted crops. Production increases came mostly from putting more land under cultivation (rather than increasing yield), a trend with trade-offs to environmental goals.

A separate evaluation (this one with AGRA cooperation) found more nuanced results but still showed a lack of impact on many key outcomes, including increased input adoption, increased sales of commercial inputs and increased farmer welfare.

With over a billion dollars in funding, we might wonder if the money could have been better spent. Is the organization ineffective? Were the goals unrealistic? Or are green revolution fixes the wrong answer to the problem?

5 objections to green revolution style fixes

Arguments against green revolution style interventions come in a few different flavors:

1. The first green revolution wasn’t as good as the story says. Which is to say, that the focus on imported seeds and fertilizer led to environmental damage, debt for small farmers and unsustainable practices that continue to harm communities. A slew of “new histories” attempt to debunk every aspect of the fairy tale***.

2. The African green revolution is missing key enablers that other regions had. Some argue that the most important input to the green revolution in Asia wasn’t mineral fertilizer but irrigation (which benefited from a huge government push). Most smallholder agriculture in Africa continues to be rain-fed, and proponents say irrigation and infrastructure would better help small farmers.

3. Many are open to improved seeds and inputs but think that system puts too much power in the hands of a few corporations, especially when it comes to GMO. The argument worries about farmer debt and dependency on a system that ultimately leads to decline in soils and yields.

4. That green revolution activities promote monocultures and mono-diets, hurting nutrition and wellness amongst those who need it the most. Monocultures (instead of intercropping, etc.) diverts land from nutritious crops and leads to less diverse diets.

5. That we have other options – organic farming, regenerative farming, and agroecology have been around for decades, with proponents advocating they can feed the world while being better for people and planet.

Pulling the pieces together

AGRA offers a concrete opportunity to look at what a well-funded effort to promote green revolution technologies can do for poverty and food security. And the answer is – not enough!

Like many organizations, AGRA considers African agriculture as backward and assumes that the right policies and markets

Like many organizations that consider African agriculture backward, AGRA assumes that the fix comes in the right policies and markets to encourage the adoption of techniques and tools used in other countries. But fairy tales are difficult to apply in reality – especially on a continent as diverse as Africa.

So who has benefitted the most from green revolution policies?

Corporations trying to sell commercial inputs into new markets, certainly. Private agro-dealers (from large to micro) that sell at the last mile generally also benefit.

Of the farmers targeted by AGRA, those with the resources and market access to gain from commercial inputs often do. These are arguments for not throwing away green revolution initiatives as failed altogether.

But for most smallholder farmers, those targeted in anti-poverty programs and whose crops are critical to local food security, the green revolution solutions can have a negligible or even negative effect. For example, seed regulations and harmonization prevent farmers from sharing knowledge and resources amongst themselves.

Furthermore, efforts to align policies and infrastructure for the commercialization of seeds and inputs diverts government attention and resources to trying different strategies – from agroecology to enhancing existing practices. This can’t be overstated, government capacity can only handle so much.

In the end, the smallholders that governments aim to help need different strategies than the ones proposed so far - either super low-cost ways to increase productivity over an extended period of time or a way out of agriculture all together.

Whether to support green revolution initiatives or its ideological opposites (in the form of organic/agro-ecology/etc.) is a false choice. The only way to truly revolutionize African agriculture will be to find the right mix of practices, without restrictions, in a uniquely African solution. Innovative small farmers are already taking the lead. Can policy makers and donors follow?

NOTES

* A quick look at government commitments to green revolution interventions: In 2006, African governments signed the Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program (CAADP), through which signing governments agreed to spend at least 10% of GDP on agricultural development. The Abuja Declaration on Fertilizer, also in 2006, set a target for fertilizer use to at least 50 kg/ha in all countries (at the time, the average was 8 kg/ha). In 2014, the Malabo Declaration reaffirmed these commitments.

Several countries also launched substantial farm input subsidy programs, which subsidize or support the dissemination and use of high-yield commercial seeds and synthetic fertilizers. Not all countries have them but those that do together spend about $1 billion per year on them – a significant effort to promote input use.

** Evaluations of AGRA’s performance. The main two reports referenced here are “Failing Africa’s Farmers: An Impact Assessment of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa” by Tim Wise, of Tufts University and a prominent critic of AGRA, and the PIATA Evaluation requested by donors and done by the evaluation agency Mathematica.

*** New histories of the green revolution include “The hungry world: America's Cold War battle against poverty in Asia”, “Revisiting the Green Revolution: Irrigation and food production in 20th century India,” “Hungry nation: Food, famine, and the making of modern India,” and “The Wide Adaptation of Green Revolution Wheat.”